Edmonia Lewis worked in the neoclassical style that was the absolutely dominant convention for creating sculptures in the 19th century, regardless of whether she worked in marble or in plaster, whether she showed the whole body of a generic human figure, or made portrait busts or profiles of faces on medallions; whether she made a statue that was table-top small or over life-size. To be frank: nineteenth-century sculptures like hers used to look just boring and all the same to me, and I have a suspicion I am not alone. This post is an attempt to sum up, in a short essay, what I have learned that allowed me to wrestle with neoclassicism in a way that made me appreciate Lewis’ work despite the fact that her style initially did nothing for me.

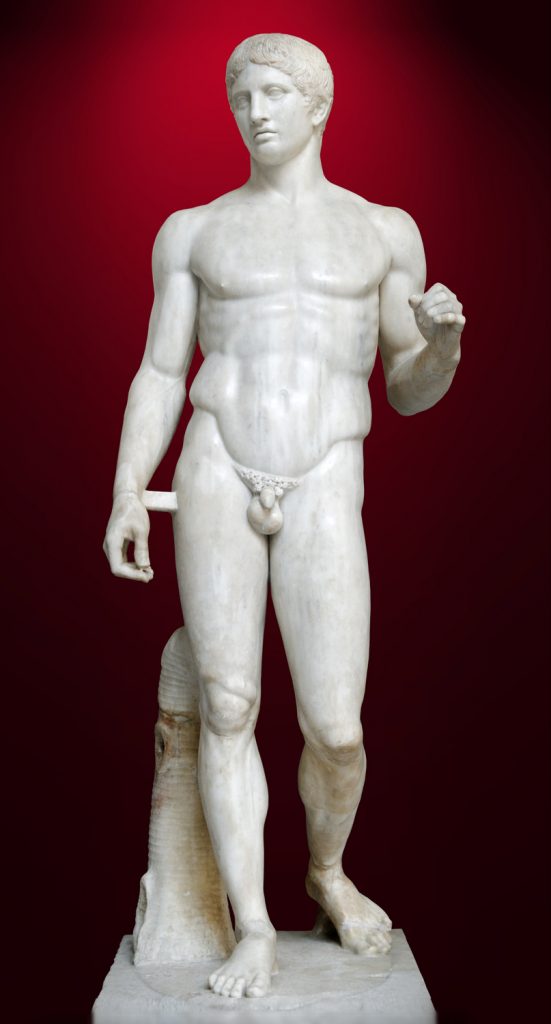

Neoclassisicism is a pretty loose term when you don’t specify the century–it refers to art based on the renewed (“neo-“) interest in ancient Greece and Rome. Technically, “classical” Greek sculpture that is supposed to be the best of the best dates to around 450 BCE (the Spear Bearer by Polykleitos, right, is often the prime example given). But in reality, Greek and Roman styles of sculpture that came after this period were also admired and imitated, and most of the available examples were actually Roman copies of Greek works, the question of what was “best” and truly “classical” about this work remained pretty murky. The general agreement was that certain body proportions, body poses (the famous cross-balance or contrapposto), and calm, stoic expressions were the ideal way of representing human bodies. Partly because most of the art that survives from ancient Greece and Rome are sculptures–specifically, Roman marble copies and variations of the Greek bronze statues that were lost long ago–neoclassical modes were especially persistent when it comes to sculpture as a medium. You can still see contemporary public monuments today that are executed in a style that evokes Greek and Roman sculpture.

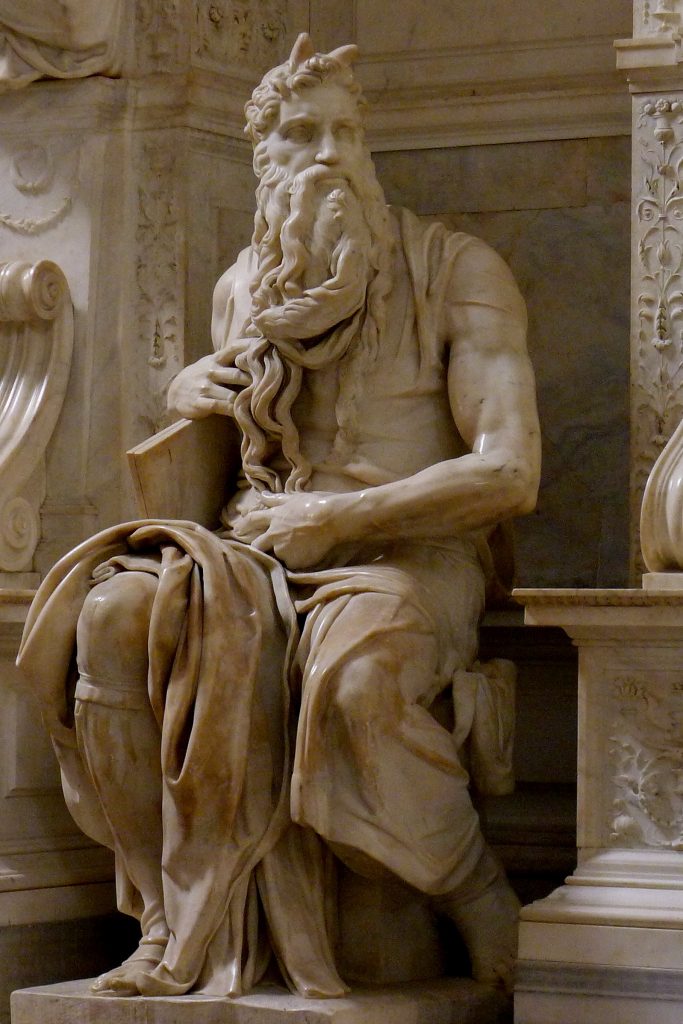

If you have a bit of a sense of standard European art history, you’ll know this superficial thumbnail sketch of the long history of neoclassicism and you can skip it: In the Renaissance (in the 15th and 16th centuries) the fascination with and imitation of Greek and Roman art and architecture became really pervasive, and artists like Michelangelo who excelled as sculptors were celebrated as comparable to the classical sculptors of antiquity. Then, the sculptors of the Baroque period (roughly, the 17th century) went a bit overboard in terms of extreme poses, gestures, expressions, and decorations–although they still use the neoclassical templates. And in the 18th century, with the Enlightenment, the so-called “excesses” of the Baroque were reined in again to make room for a simpler, calmer, and more “rational” approach to imitating Greek and Roman art. The 18th century was also the time when Greek and Roman sculptures were more carefully distinguished from one another and then sub-classified into many different periods, with scholars in the wake of the German “father of art history,” Johann Jakob Winckelmann, positing for the first time that “Greek” originals were superior to “Roman” copies.

When it comes to the 19th century, the neoclassical tradition continues, with sculptors now quoting and imitating not just the famous works by the Greeks and the Romans (which were admired in the museums of Europe, foremost the Louvre and the Vatican Museums, but also elsewhere in popular and ubiquitous plaster copy collections), but also the neoclassical art of earlier centuries, above all, Michelangelo’s sculptures from the Renaissance (like the Moses shown above, which I included because Edmonia Lewis produced a copy in 1875–just in case you are wondering why I didn’t include the more famous David instead).

The overall effect was that 19th-century sculptures can look especially imitative–like copies of copies with other copies in mind to the untrained eye (mine included). Innovations were often very gradual and very cautious, and often had to do with refinement, with changes in scale rather than style, or with the application of the neoclassical “look” to a new theme that was considered daring. A sculptor might become famous for ever more polished or finely carved marble, for making a particularly large (“colossal”) neoclassical sculpture, or for representing a modern politician as a Roman general (as the famous sculptor Antonio Canova did with George Washington in his 1821). Even slight deviations could be seen as groundbreaking and even scandalous innovations, for example when the British sculptor John Gibson experimented with tinting his marble for a sculpture of Venus. These small-scale variations in a very homogenous style sometimes make it difficult to see what was interesting about neoclassical works–partly because around the turn to the 20th century, the whole idea of what was good in art shifted, basically, from “following the rules, with variations” to the notion of art as avant-garde, “breaking all the rules and coming up with the next new thing.”

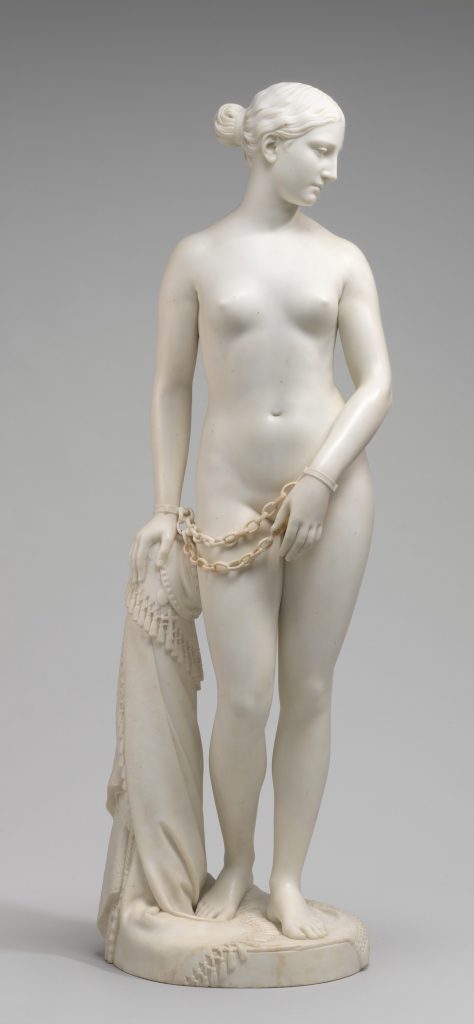

National Gallery of Art. Image credit: nga.gov

American sculptors of this time in particular were often celebrated because they excelled at executing their work in the neoclassical style, not because they are original or break with precedent. (This is also why they are primarily a specialty of art historians, and not particularly well-known anymore.) They also needed to walk a fine line: on the one hand, they wanted to show off their classical (read: European) training, which revolved around mastering the “classical nude” (male and female); on the other hand, they had meet the demands and cater to the taste of American patrons, public and private, whose attitude to nudity was often much more Puritanical than that of Europeans, not just when it came to full-frontal male nudity (often strategically concealed even in Europe). The result of trying to strike a balance between these two was the “chaste nude”–naked, but saved from the idea that they were erotic by the association with classical Greek statuary, by being “high art.” The most famous example is Hiram Powers’ Greek Slave. The woman, representing a captive by the Ottoman Turks, was seen as an emblem of moral purity (her nudity fully to blame on her captors), and hugely popular in the US even though it was the first fully nude female sculpture made by an American to be publicly exhibited.

The handful of American women sculptors of the 19th century are introduced in a separate post–but they had in common with the larger and more famous group of male sculptors that they worked in the neoclassical style. Some of them produced the kind of “chaste nudes” that some of their male compatriots, most of them fellow expatriates in Rome and Florence, were famous for. For example, Louisa Landers, Anne Whitney, and Harriet Hosmer all created male and female figures that were at least partially nude (although some of them are lost). But their roles as female sculptors were already precarious, and they often embroiled in scandals or satirized because they were women sculptors (especially if they were single, and even more so if they defied convention in terms of dressing in more masculine ways, or in not trying to conceal that they were in a same-sex relationship). So they could often ill-afford to violate norms about women not representing human figures in the nude, and possibly drawing on live models. It is not surprising that they often opted for clothed subjects, like Harriet Hosmer’s Zenobia–another captive in chains, like Powers’ Greek Slave, but in full regalia.

Edmonia Lewis went further than many of her female fellow sculptors in avoiding nude female figures in her otherwise thoroughly neoclassical marble figures. The closest she came was in the Death of Cleopatra, where the dead queen’s exposed breast is probably mostly about emphasizing her similarity to dying Amazons in antique sculpture–and in that respect sidesteps (or distracts from) the question whether we are seeing the death of a lascivious queen or the chaste nudity of a dead captive woman. The post on Forever Free addresses the assumption (very common in the scholarship on Lewis) that as a woman of color she may have felt the need to steer away from anything that could evoke the racist sexualizing of Black or Indigenous women. That would have not only meant that she avoided representing women with ethnic traits, as I discuss in the post, but also showing nudity.

While we cannot know for sure how important this was in creating Lewis’ “conservative” neoclassical style, which was very likely also her choice because it was what sold and got attention at exhibitions and auctions: it was the going and popular style in the 1860s and 1870s. There is at this point no evidence that she ever tried to go beyond this style–the only work we know of past the early 1880s is the lost (or possibly never made) bronze bust of Phillis Wheatley that is mentioned as a work commissioned in 1893. But without more work coming to light, we have to assume that it took the next generation of Black female sculptors, in particular Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, to step out of the comfort zone of neoclassicism. In sculpture, the radical break with the old and now quite tired neoclassical tradition began with Auguste Rodin, who was of the same generation as Lewis (he was born in 1840 and died in 1917), and started to work in a new style in the 1870s, when Lewis and many others were still creating neoclassical “ideal sculpture,” as it was also known. By the 1890s–the time of Art Nouveau, Aestheticism, the Fin de siècle, or Decadence–artists became more admired, even worshipped, for being rebels and going against established conventions. Rodin’s (and the Impressionists’ and Symbolists’ and Aesthetes’) Bohemian Paris was, for a decade or two, the hub of much of this change. Lewis did live there in the 1890s, but she had faded out of the public eye, and as far as we know, she never became part of the new, rule-breaking style in art and sculpture.

A Note on Further Reading

There is much more to be said about the representation of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color in Western art since antiquity, in 19th-century art, and in 19th-century American art. The racism of neoclassicism and of the “Greek ideal” (including in Winckelmann’s writing) is incredibly important to consider in thinking about this, because they were so often publicly displayed, including as outdoor monuments. A number of important book-length studies have been written about sculpture, race, and gender. They are not all included on the Resources page, because my focus is on Lewis, but Farrington and Collins are a good starting point for thinking about the representation of Black women in art in general. On race, gender, and 19th-century sculpture, Nelson’s The Color of Stone is especially important, and when it comes to female sculptors in Rome, Dabakis’ A Sisterhood of Sculptors is indispensable. The double figure of the queen and captive in 19th century sculpture is key to Kasson’s older (1990) study.

Your Turn

This post reads a bit like a textbook, and is therefore also just skimming the surface. But was an overview like this helpful? What surprised you most or was completely new to you, if anything? What is most glaringly missing, if you know about this already? And what does it make you want to learn more about?

If you are a fan of neoclassicist sculpture: Where am I being unfair to the style? What do you like about it, and what should I learn to appreciate more?

This is interesting & helpful to me as a historical novelist studying artists and writers in Europe during the mid-19th century. I was seeking more information about Edmonia Lewis and her sculptures and had wondered if she ever did a sculpture of Zenobia. I love seeing her work in the context of Neoclassical art–I’ve read a great deal about Hiram Powers, Harriet Hosmer, William Wetmore Story, and Robert Barrett Browning (Pen), but what I’ve read puts them in a social and biographical context. Thank you for your work on this subject, and for the references to learn more.

Thank you, Laura! There is no reference to Lewis ever working on a Zenobia–I think that given that Zenobia was not nearly as well known as Cleopatra, that Hosmer’s “Zenobia in Chains” was so famous, and that Lewis knew Hosmer, that would have been seen as too imitative (even in the context of Neoclassicism), unlike a Cleopatra, of which there were so many different representation. But several scholars assume that even the choice of another “trapped” female ruler (i.e. Cleopatra) was influenced by “Zenobia in chains.” I am sure you have seen Melissa Dabakis’ fabulous book on the women sculptors of Rome? Lewis is not really a major focus of her discussion, but the context for Hosmer and several other women is really well represented. I’m intrigued by your reference to Pen–I know so little about him even as I know quite a bit about his parents (for a non-expert on poetry, at any rate), but I understand he was instrumental in preserving the Brownings’ apartment in Florence, which is now a little house museum that I had the good luck to visit just before the pandemic.

Did Edmonia Lewis do small head statue ( white marble) labeled Arrow Maker?