Female sculptors are rare, even rarer than female painters, throughout all of art history–even today, there are significantly fewer female sculptors than painters, although 20th-century movements in art have of course complicated the idea of “sculpture”–and women ceramicists, fabric artists, collage artists working in three dimensions have all contributed to destabilizing the idea that sculpture has to be made with the “masculine” materials of stone or metal.

The gendering of sculpture as an art form is a complicated thing, and others have written about how “unfeminine” it was considered to be a sculptor in the 19th century much more articulately than I can. Here is a starting point: The idea that women were not capable of physically challenging labor such as carving marble or casting bronze (working in clay or wax was, for the longest time, considered preliminary work) has a long history, and it went hand in hand with obstacles and outright prohibitions women encountered if they wanted to train in a trade or attend art-school classes that involved such work. There was also the fact that sculpting, into the 20th century, typically involved working with a crew of trained male laborers (who were doing the chiseling, casting, and forging for you, or at least with you, if you were the sculptor), and the idea that women would be in a position of being in command of such a crew was thought of as inappropriate.

Given all of this, it is nothing short of amazing that there were women sculptors in the 19th century at all. Here is a preliminary list.

The fact that almost all of them worked abroad, mostly in Rome, in a sort of “artist colony,” where they could (in theory) support each other in their artistic practice is perhaps not surprising. Many of them (not just Edmonia Lewis) are on record claiming to feeling more free in Europe than in the US as women artists.Given the main focus of this site on Black history, I have tried to point out even in these thumbnail sketches whether they were at all involved in or responding to questions relating to abolitionism and the situation of Black Americans after emancipation.

(If you are curious about forerunners, Patience Wright, 1725-1786, was one of the very first American sculptors ever, making figures of tinted wax that were then dressed in costumes, a decade or so earlier than the famous Mme Toussaud.)

Emma Stebbins, 1815-1882

Stebbins was from New York City. One of many children of a wealthy family, she was able to study painting and drawing and started exhibiting her work at the National Academy of Design and at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. went to Rome in 1856 and stayed, becoming part of the circle around Harriet Hosmer and her patron, the actress Charlotte Cushman. Stebbins and Cushman became a couple and lived together until the end of Cushman’s life in 1876. She made mostly smaller marble sculptures, but she was also the creator of Angel of the Waters, the figure on top of the Bethesda Fountain in Central Park.

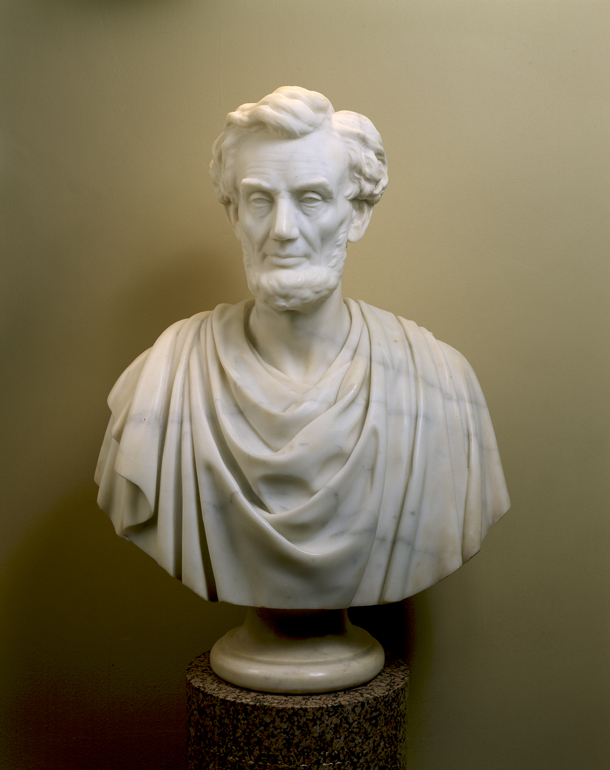

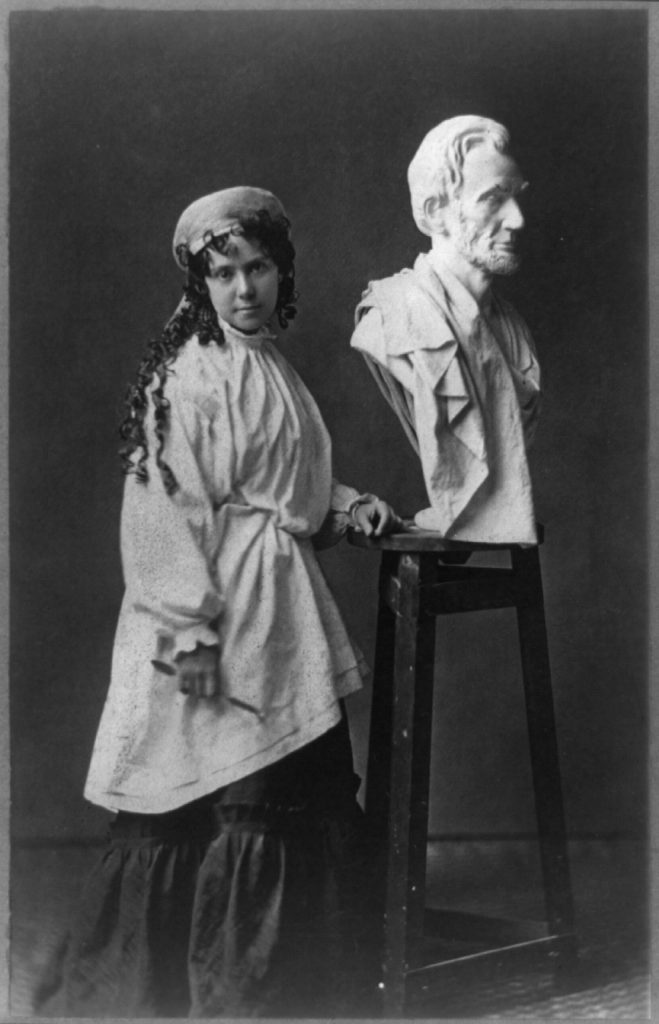

Sarah Fisher Ames (née Clampitt)

1817-1901

Ames studied art in Boston and Rome, one of the first American women sculptors to travel to Rome–sometime in the 1840s, in the company of her husband, a portrait painter. She became famous for several busts of Abraham Lincoln, whom she got to know personally when she worked as a nurse in the DC area during the Civil War . One of these is a marble bust now in the US Senate collection. Late in life, she was one of the female artists whose work was exhibited at the Woman’s Building of the World’s Columbian Exhibition in 1893.

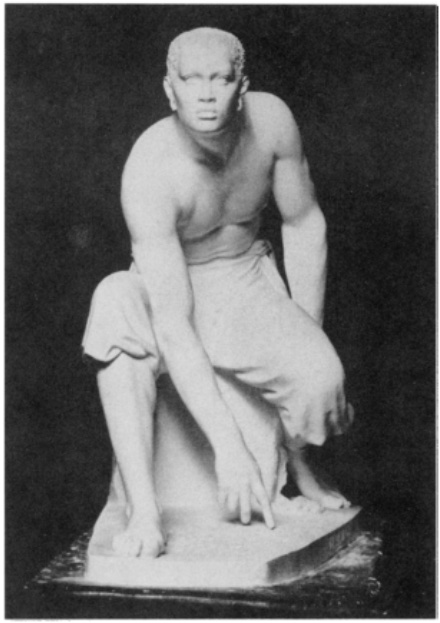

Anne Whitney, 1821-1915

Whitney was a poet as well as a prolific sculptor, and a liberal activist in favor of abolition and women’s rights. Originally from a wealthy Unitarian family in Massachusetts, she sought training in anatomy in New York and was able to study at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia, but after a few years in Boston in the 1860s, she moved to Rome, where she was working in the same circle of expats as the other female sculptures of her generation. She returned to Boston in 1872 and shared her life there with Abby Adeline Manning in what was called a “Boston marriage” (often, but not always, code for a long-term lesbian relationship) while continuing to work on her art. Some of her sculptures became public monuments, including abolitionist Charles Sumner in Harvard Square in Boston. A sculpture portraying the Toussaint Louverture, the leader of the successful slave revolt in Haiti, was lost (but the blurry photo of it that survives is captivating, so here it is).

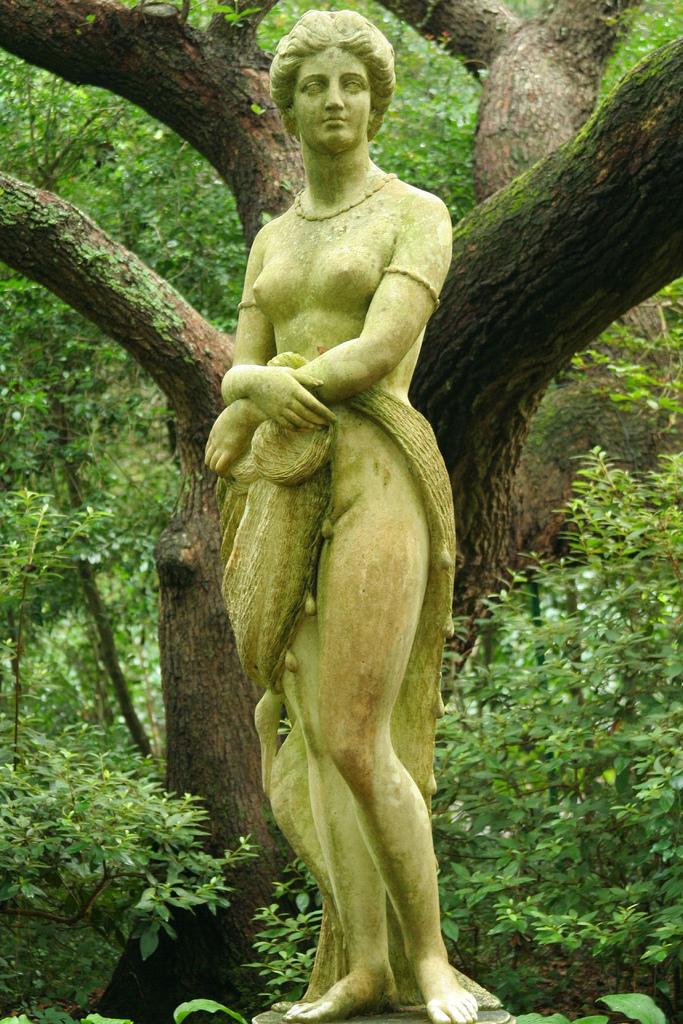

Louisa Lander, 1826-1923

Lander was from Salem, Massachusetts, and took an early interest in carving, becoming a professional cameo carver in Boston like Margaret Foley (although, unlike Foley, she was from a wealthy family). She went to Rome in 1855 and joined the women sculptors around Harriet Hosmer and Charlotte Cushman, and became a student of the American sculptor Thomas Crawford. But she was embroiled in rumors about a possible affair or posing as a model in the nude. She left the community of women sculptors in Rome, and eventually returned to the US for good in 1860 and established a studio in Boston. During the Civil War, was active as a nurse in D.C. As with Edmonia Lewis, her later life (beginning in 1871) is not well-documented. Her 1859 sculpture of Virginia Dare, the semi-mythical “first English child” born in the Americas, who perished with the Roanoke colony, is on display in the Elizabethan Gardens in Manteo, NC. Virginia Dare, now a problematic figure sometimes associated with white nationalist extremists, was one of many representations of “captive women” in the mid-19th century (see Dabakis for a good analysis of her sculpture and also the scandals surrounding Lander, 67-81). But Lander’s interpretation of this theme takes more risks with nudity than most sculptures by women from this time–especially compared with Harriet Hosmer’s fully clothed Zenobia in Chains.

Margaret Foley, 1827-1877

Foley was from Vermont and, unlike most other women artists of her time, she was not wealthy. She started out as a factory girl in Lowell, Mass., and then became a professional carver of cameos and attended the new School of Design for Women that opened in Boston in 1850. She carved cameo portraits of several abolitionists and was supported by the Boston community of liberal reformers. She was able to join the group of artists in Rome around Hosmer and Stebbins in 1861, and settled in Rome, specializing in medallion portraits, cameos, and occasional marble busts, for example this Cleopatra, completed shortly before her death, and exhibited, like Edmonia Lewis’s Cleopatra (along with several others) at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition.

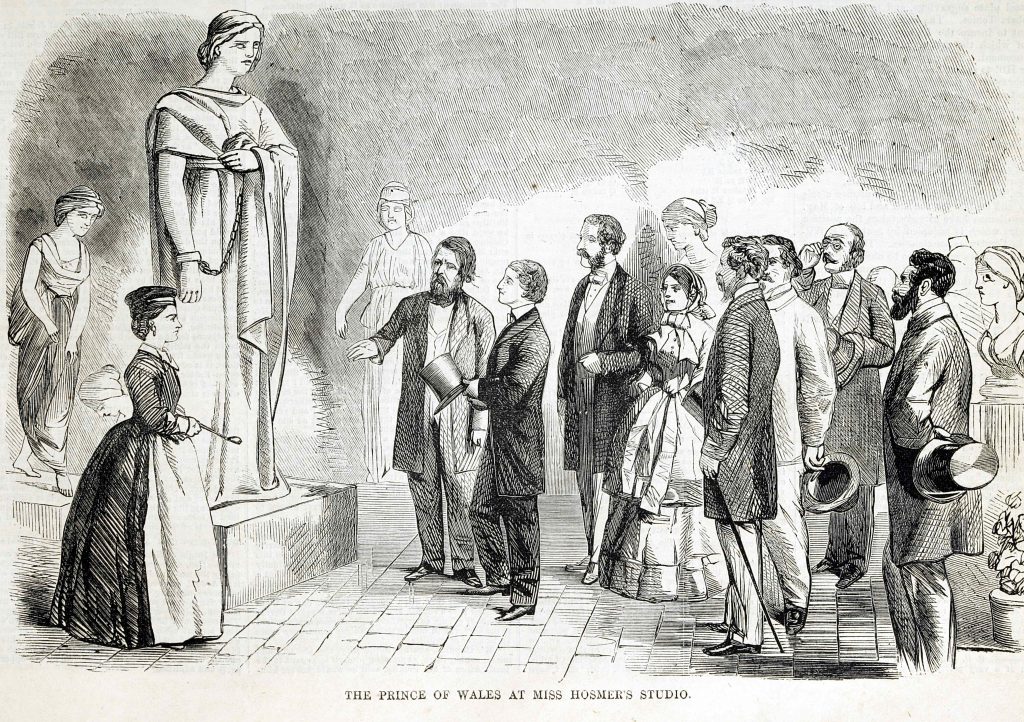

Harriet Hosmer, 1830-1908

Hosmer, from an affluent Massachusetts family, studied sculpture in Boston and then in Rome, where she lived among other American sculptors for many years; later, she traveled back and forth between the US and England, where she was especially popular: She had a studio there, and a complicated love relationship with an English aristocrat and collector, Louisa Baring, Lady Ashburton. Her neoclassical work was influenced by Hiram Powers and John Gibson (under whom she studied in Rome); but like many female sculptors of the time, she mostly shied away from nude figures. Her Zenobia in Chains (1859), representing a Syrian Queen who became a Roman captive in the 3rd c. CE, is one of her most famous works and sometimes read as a statement relating to abolitionism or to women’s rights.

Edmonia Lewis, 1844?-1907

You already have the information about her at your fingertips! However, it’s worth noting that many of these other women sculptors knew her in Rome. She was part of their social circle, although she may very well have experienced racist prejudice and could have distanced themselves from the group over time, as she stayed on in Rome even after many of them had left. It’s also important to remember that in the 1890s, she lived (at least briefly) in Paris, just before the arrival of Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (and Henry Ossawa Tanner)–and just as Paris was becoming the center of the new art movements (aestheticism, symbolism, art nouveau) that were to transform the style of sculpture as well as painting dramatically from the neoclassical style she practiced.

Vinnie Ream, 1847-1914

Vinnie Ream was born in Wisconsin, but moved to D.C. when still a teenager, and studied under the American sculptor Clark Mills. She received a prestigious government commission to make a full-size marble sculpture of Lincoln in 1866 (the sculpture, from 1871, is in the Capitol Rotunda). She spent time in Europe while creating it, including a longer stay in Rome, where she was part of the group around Hosmer and Whitney, but was embroiled in various scandals. She later had studios in New York City and then again DC, showed work at many major exhibitions (including three at the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago). But as per the common social conventions of the time, she did not create much work after she got married in 1878.

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, 1877-1968

Fuller, an artist from Philadelphia, who went to Paris in 1899 for several years, is included here even though she is properly a 20th-century artist, because her very earliest works were created in the 1890s–a small wooden sculpture she made as a teenager was even exhibited at the World’s Columbian Exhibition of 1893. Unfortunately, most of her early works have been lost (due to a fire in the 1900s in a warehouse where they were stored), but some photographs survive. Both Lisa Farrington and Judith Wilson see her as a direct descendant of Edmonia Lewis, although her style, influenced by Rodin, was quite different–she is the Black sculptor who breaks with neoclassicism, but unfortunately, her gender and her race put her on the margins of the art world. I became fascinated by her and the differences and similarities between her and Lewis, a generation apart, but also divided by a watershed in sculptural art. You can find out much more about this here.

May Howard Jackson, 1877-1931, sculptor

Like Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Jackson was from Philadelphia, studied at the Pennsylvania Academy and exhibited some of her very earliest work in the 1890s. Like Fuller’s, most of her work postdates the 19th century. But unlike Fuller, she did not study abroad, was sometimes overlooked as an important female Black sculptor. She lived in D.C., where she knew many African-American intellectuals from the Harlem Renaissance, and many of her sculptures are portraits of these friends. She was, intriguingly, the aunt and sometime foster parent of Harlem Renaissance sculptor Sargent Johnson (1888-1967) and had a big influence on him.

Discovery / Resource Note:

I knew absolutely nothing about these women until just about two years ago, and beyond the American artists that I am listing here, I have not (yet) explored further. I learned about most of these sculptors (and the details of their lives and work) from Melissa Dabakis, and about Fuller and Jackson from Lisa Farrington (see my resource page). Several more female sculptors from the US are on record as having their work featured at the World’s Columbian Exhibition of 1893, but even now, we often know little about them except their names. But more and more research is being done in this understudied field. For example, in early 2021, the UK-based Public Statues and Sculpture Association (PSSA) held a spring and a fall series of on-line talks on “Discovering Women Sculptors,” from the 17th to the 20th century.

Your Turn:

Which of these female sculptors are you most curious about, based on these sketches? Did you know any of them beforehand? Do you remember where and when you first came across them? Had you ever thought about what you know about women artists in terms of medium (painting vs. sculpture vs. …)? In what context?

And what about the connections between these artists? What makes them intriguing (or confusing, for that matter)? What kinds of questions do these connections generate?