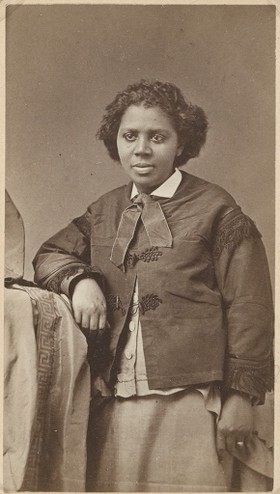

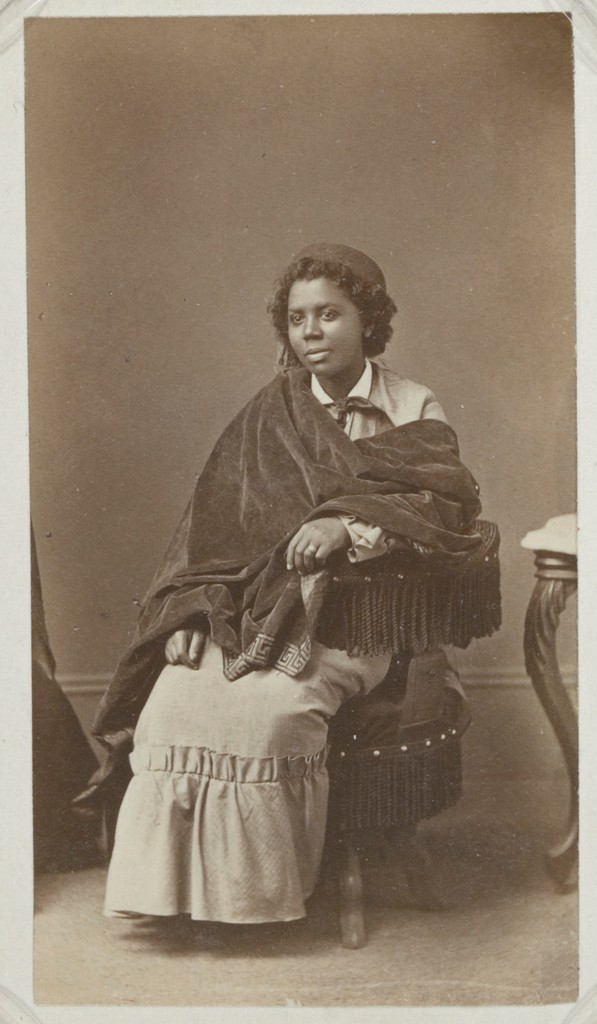

The gallery below features all the photographs of Edmonia Lewis that have been found so far, as far as I have been able to find out. They are all so-called cartes de visite, small photographic prints mounted on cardboard (about 3.75 by 2.25″ or 9.5 by 5.7 cm) that functioned as business cards, often handed out to potential patrons as well as friends. As you look at them, I wonder what they make you think about. I have thought about these prints a lot, and I hope to write a longer blog about them. I end with some of the questions that I have been asking myself.

Two cartes de visite from Boston (date unknown)

Boston, Massachusetts, n.d. ca. 1864-1872.

Boston, Massachusetts, n.d. ca. 1864-1872.

The Henry Rocher photo session (Chicago, 1870)

The carte de visite from Rome–found in 2011

My Questions

Edmonia Lewis was beautiful. I love looking at her face, the way she seems at ease in front of the camera in some of these, the hint of a smile in some of the photos, from a time before the full-on toothy smile was thought proper for any formal portrait. I keep wondering which of these photos she liked best, and why–which of these she gave to friends and, above all, to current and potential patrons and collectors. These photos were taken, at some expense, for this kind of self-promotion. What kind of image was she projecting here; how was it supposed to help her advertise her art, and herself as the artist?

The photographer of the series taken in Chicago, Henry Rocher (1826-1887) specialized in taking photographs of actors and performers, and what made his studio special were his many props and costumes. I know no more than what the link above can tell us, but I have been wondering about the costume and the props Lewis and Rocher chose, presumably jointly, for her to use. I find some of the details fascinating: Why the Turkish fez and the vaguely oriental jacket? Why the blanket with the Greek meander pattern? How unusual was it to be so theatrical about one’s outfit in a photo session? And why cover her body in so many layers of cloth, both here and arguably also in the later photo from Rome? I have tried to reflect on how that contrasts with showing much more body in the sculptures she made (although her adult figures are never wholly nude), and I want to work that out a bit more before I write about it.

And then, even more importantly what role did racial identity play in the way she presented herself in these photographs? Interviewers always mentioned her racial background in one way or another, and called attention to her physical features in ways that can only come across to modern readers as racist, but that can also be very complicated. The pertinent example is–surprise!–the texture of her hair, still such a complex and much-discussed issue for Black people. A writer for the British Art-Journal (Vol 32, 1870, p.77) writing about the studios of “lady-sculptors” in Rome claimed that “On one side of the head the hair is woolly, her father having been a negro; on the other, it is of the soft, flaccid character which distinguishes the Indian race, from which her mother sprang.” This seems bizarre. But here is the complicated bit: the reviewer does not, in fact, refer directly to Lewis’ hair, but to the sculpted rendering of it in a portrait bust of Lewis made by her friend Isobel Cholmley –in other words, he is talking about a stylized representation of her hair in art, and one that probably had Lewis’ tacit approval, since she sat for this bust made by her friend. But as I now look at her hair in the photographs, I wonder whether she wanted to emphasize this idea of a visible “dual hair” heritage with the way she wore her hair; whether wearing the fez-like cap was a way to get away from the hair question, and so on. These are not questions with answers, but they point to the larger question about of how 19th-century Black and Indigenous women get represented in photographs (or portraits in general), what control they might have over this representation–here, presumably a lot, but it’s still the photographer who takes the picture–and what role their ethnicity plays in this.

That leads to the bigger question of the role of photography, especially when it came to the ways Black people were represented in photos, and how much control they had, in general and in specific cases, about this. Specifically: What do I need to know about cartes de visite and who used them? When photography became commercially viable and affordable in the 1840s, the need for portrait painters who produced “images from life” basically vanished. Initially, sitting for a photo portrait was quite expensive and unusual. But these little photos, 8 on per negative, and printed in a small enough format to be fairly inexpensive and easily mailed, became incredibly popular after their invention in the mid-1850s. But what did they cost to sit for and who had them made? You may have seen some of the famous cartes de visite of Sojourner Truth. But how common was it for African-Americans to have these taken, and how did that change after the Civil War? Who typically controlled the pose and outfits? How much agency did the sitters have? That last question seems especially important for the kind of self-promotion that Edmonia Lewis was clearly looking for, in all three photo shoots (and perhaps others that have not been found), because as in the interviews she gave to reporters over the years, she would have wanted to have some impact on what would be literally her “image”–did she insist on experimenting with cap and no cap, and with the various bulky and shapeless items–the jacket, the blanket–that hid her body more than it showcased, or was this dictated by the photographer?

I find this really intriguing to mull over, so these are research questions I am currently trying to find answers to in the vibrant and fascinating research on 19th-century photographs of Black people (and also BY Black people), on the role of the carte de visite, and on the collectors of such cards.

Your Turn: What are your questions?